College Essay Writing Tip #1: Write First, Think Later

Gabrielle Glancy takes the common complaint, “I’m Stuck! I have nothing to say!” and turns it into an opportunity for total creative generation. Because Glancy is as pragmatic, funny, and as experienced as coaches come, she reminds us that “our” best ideas are born from a rich matrix of unknowable origins and that you’re guaranteed to get a “better” college essay out of this, and more than you could have ever asked for. She’ll convince you, and you’ll show yourself, that the best already lies within you.

Many people will tell you that you need to start with a topic, and start with an introduction.

I cannot think of a more sure way to gum up your brain than this!

You may have an idea of what you want to write about. You may have read the prompt for a particular school and have had thoughts about where you might take this essay. That’s good. Nothing to worry about or cancel out.

But what do you do after you’ve brainstormed a topic?

In my work with students who are stuck, I don’t say: Come on. What’s wrong with you? Can’t you just start writing?

Rather, I turn writing into a game.

It’s worth noting here the difficulty in deconstructing a process with the thinking mind that does not involve the thinking mind.

That’s like hearing the sound of one hand clapping. It’s a built-in conundrum.

In my experience, play is the best way to create opportunities for a chance or accidental moment of inspiration to occur.

Once the words start flowing, I keep quiet until the stream runs dry. At that point, when the student has written as much as they can (for the moment), I say something like: How do you feel in your body? What does it feel like to write this way?

This approach is completely counter to what most people will do. Even the most enlightened writing coaches will tell you that you need to have a topic to begin. They will have you brainstorm topics — your favorite object, what you want to be when you grow up — and then they will say something to the effect of: “Great topic! Now write your essay!”

But how do you do this?

The problem is that once you engage the “critical” part of the mind — the part that is concerned not with the journey but with the destination — you are creating an environmental inhospitable to creativity/innovation/newness.

From there, it is very difficult to generate ideas, let alone craft an essay from first word to last (starting with the introduction!)

So what do I do instead?

I have them write first in the worry-free zone. Almost anything can generate writing.

Recently I gave a talk in an auditorium in which there was a white board that had three words on it: “Grass. Bunny. Hamster.”

I have no idea why these three words were there, but I used them to my advantage.

I asked the students before me to vote on one of these words. They chose “hamster.”

I then directed them to free write on the word hamster. “Write anything that comes to mind when you think of a hamster. Don’t worry about grammar or punctuation, just write.”

There were sixty students at this workshop. They all produced unique writing on the subject. And believe it or not, many of them wrote about topics they could potentially develop into narrative personal statements — the time my hamster got his head caught in the treadmill, the week we lost our goldfish, our hamster and our dog . . .

Then I bring to the students’ attention the feelings they have just experienced— flow, inspiration, being in the zone, whatever you want to call it — so they become conscious of what they felt in their bodies and can come to call upon the memory of this experience as needed.

This is not unlike the moment Gallwey describes of reproducing a peak experience in his book The Inner Game of Tennis:

One day when I was practicing this form of concentration while serving, I began hitting the ball unusually well. I could hear a sharp crack instead of the usual sound at the moment of impact… I resisted the temptation to figure out why, and simply asked my body to do whatever was necessary to reproduce that “crack.” I held the sound in my memory, and to my amazement my body reproduced it time and again.

The idea is to happen upon the flow through play, and then make conscious your experience of being in the flow, until the day comes when you can reliably, through “body memory,” tap into the trance-like state pretty much on cue.

When you’re in the zone, you almost feel like a channel, like the writing is coming through you.

Writes Gallwey regarding tennis: “Commonly students use language like ‘I wasn’t there,’ ‘Something else took over,’ ‘My racket did this, or did that,’ as if it had a will of its own. But the racket wasn’t missing, and the great shot was not an accident . . .”

What I am describing here is very important.

It is the idea that you must put the thinking mind aside to write well. How do you do this?

You write first — on just about anything — and then you read what you’ve written to figure out what you’re trying to say.

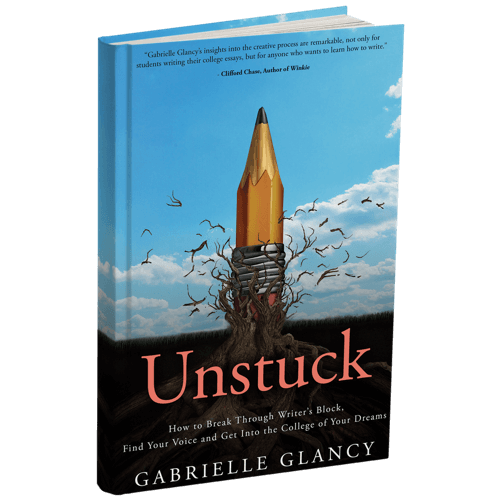

This is described in my book UNSTUCK and is a great way to . . . well . . . get UNSTUCK!

I’d love to show you how I teach this and how you can learn this. Click here to book an appointment. This way of doing things is a heck of a lot easier than trying to figure it all out before you get anything down on paper!